I listen to Chopin when I drive. My most recent find - all the etudes recorded by Louis Lortie (You Tube recording of Lortie ). The three dramatic ones at the end of Op. 25 are, as a set, a particular favorite. His timing is impeccable and the drama in the music well balanced with the classical perfection of form.

Another favorite CD that I recently returned to is of the two Piano Concerti with Krystian Zimerman at the keyboard, conducting his specially assembled orchestra - Polish Festival Orchestra. The clarinetist from that orchestra, Jan Jakub Bokun, has told me about the experience of rehearsing and playing with the Maestro. It was very strenuous, but immensely rewarding. One phrase, one detail, would take a long time to polish - sometimes aggravatingly long time. It had to be done to perfection... and it was. Just listen to the miraculous details - bringing out inner voices, phrasing, expression... Zimerman's Chopin is a true romantic, quickly moving from one emotional extreme to another, from enchantment to torment. An astounding vision of grand proportions. These are not little pieces of "stile brillante" provenance, ornamental, made to please. These are powerful expressions of the soaring human spirit.

OK, let's leave it at that. The spirit... What about the spirit? First, let me reflect on the spirit of Polish pride. To welcome the year 2010, just as I was finishing the "Chopin with Cherries" anthology that gave rise to this blog, I went to friends' house for a New Year's Eve Party. I never spent that time with this particular family and wanted to do something different, something I had not done before. It was interesting - filled with children and games, not serious adult dinner conversation and dancing.

But one dance captured my attention and remained in my memory: Chopin's Polonaise in A Major, Op. 40, nicknamed "The Military" (the link points to a YouTube recording by Maurizio Pollini). Yes, the same Polonaise that gave its first notes to a signal of the British broadcasts to occupied Poland during World War II. And here we are, dancing? Just after midnight all the guests at the party lined up in a long line of couples, the host sat at the grand piano and off we went. Around the living room, out onto the patio, up and down the steps, out one door, in another, all over the house... The moon was unusually bright that night, surrounded by an enormous halo, a portent of things to come. I felt a rush of pride, elation even, when we moved along with dignity, in triple meter: one long step with bended knees and two short ones. Down, up, up, down, up, up, around the house, around the world... It was so incredibly moving - a small group of Poles and their international rag-tag bunch of friends dancing to music written almost two hundred years ago and heard in so many homes, on so many concert stages. Welcome the new year, the year of Chopin! That was two years ago - and the tradition of dancing that particular Polonaise at midnight continues.

On the way back home, I drove through an unfamiliar neighborhood and saw boys playing with a bonfire on the front lawn of their small house. It was a working class neighborhood with tiny houses squished in neat rows on streets leading up to the hill of the Occidental College. The moon, the fire, the dance - I was inspired to write a haibun about it. It was recently published in an Altadena anthology, Poetry and Cookies, edited by Pauli Dutton, the Head Librarian of the Altadena Public Library:

Midnight Fire

In the golden holiness of a night that will never be seen again and will never return… (From a Gypsy tale)

After greeting the New Year with a Chopin polonaise danced around the hall, I drove down the street of your childhood. It was drenched with the glare of the full moon in a magnificent sparkling halo. The old house was not empty and dark. On the front lawn, boys were jumping around a huge bonfire. They screamed with joy, as the flames shot up to the sky. The gold reached out to the icy blue light, when they called me to join their wild party. Sparks scattered among the stars. You were there, hidden in shadows. I sensed your sudden delight.

my rose diamond brooch

sparkles on the black velvet -

stars at midnight

© 2010 by Maja Trochimczyk

I wrote more verse about the Polonaise itself, but all the descriptions fell short of the delight I felt that night, so it was reduced to just an introduction to a story that has no end. The contrast of warm flames and icy moonlight was unforgettable. I added the romance, of course - poetry is not supposed to be real, though, when rooted in an actual experience it touches a nerve in listeners. After one reading I was asked by an eager member of the audience: "So what about the man who gave you that brooch? Where is he now?" "There was no man. This is my brooch, I got it for my daughter and it returned to me," I said. There was nobody lurking in the shadows. . . The poem sounds better this way, though.

Fast forward two years, and I'm playing recordings of Chopin in jail. This is the path that I took, and this is where it is going. . . forward. My students are inmates who have completed the Sheriff's Education-Based Incarceration program, and are approaching dates of their release after completing their sentences. I do not ask what they are in for, it does not matter. What matters is that once released they never come back. Jailing them is a huge cost to society and committing crimes does not help them or anyone else. It is just not the right thing to do. But many offenders keep returning to jails, keep doing the same thing that they were always doing. My approach to changing their thinking, their image of self and the world, involves classical music. Chopin, in particular. Due to his serious illness, dying of TB, composing between fits of coughing and spitting blood, he can be an example of heroic courage. William Pillin expressed this idea very well, in his poem "Chopin" (included in the Chopin with Cherries anthology):

Chopin

(excerpt from a poem by William Pillin)

White and wasting he dotted

with splashes of blood his lunar pages,

carrying death like a singing bird

in his chest, his tissue held together

by dreams and bacilli. “I used to find him,”

wrote George Sand, “late at night at his piano,

pale, with haggard eyes, his hair almost standing,

and it was some minutes before he knew me.”

In Majorca, the doctors

shuddered at his blood-flecked mouth,

burned his belongings, compelled him

to take refuge in a former monastery.

“My stone cell is shaped like a coffin.

You can roar — but always in silence.”

When it stormed he wrote the ‘raindrop’ prelude

and from the thunder he fashioned an étude.

*

“I work a lot,” he wrote to his sister,

“I cross out all the time, I cough without measure.”

With death’s hand on his slender shoulder

he created ballades, études, nocturnes.

Chopin had what it takes to succeed against all odds. He used his time well - he created something lasting that speaks to us two hundred years later. They can do it too. It is heroic courage that is needed to succeed when you leave jail with a felony record, no friends to turn to (because those you had would bring you straight back to jail and those you hurt would not speak to you again), no home, no job...

America is very punitive. Not only does it have the highest rate of incarceration in the world: one in thirty one adults is under correctional supervision, well over 700 people per 100,000 adult residents. The second highest rate is in the second most punitive country, Russia. There, about 500 inmates are locked up per 100,000 of adults. Other countries have a fraction of that. The "war" of imprisonment was clearly won by the U.S. There are serious societal costs associated with that dubious victory. The stigma of having been once in prison or jail remains and permanently marrs the record of an individual who has virtually no chance for redemption. Job applications feature a box: have you ever been incarcerated, or committed felony, or misdemeanor? Once you check the box, the application lands in the garbage bin. I tell my students behind bars that they have to be really tough to ignore the rejections and insults that will come their way. Their sentences are finished but the stigma is there and will bring them back if they do not fight it by having the courage to be good.

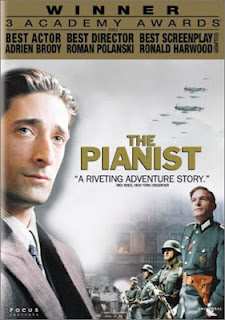

Chopin helps here. How? We listen to a Nocturne and then to the same Nocturne played by The Pianist's Adrien Brody in an old-fashioned suit. The camera pans out to show the engineer's booth. This is a live broadcast of the Polish Radio in Warsaw. This is September 1939. Soon the bombs begin to fall, the pianist initially refuses to stop playing but has no choice. He falls off the bench, the building is destroyed by German bombs, and his odyssey begins. The astounding, true story of survival against all odds - the story of Wladyslaw Szpilman, as told by Roman Polanski (another Holocaust survivor) leaves the incarcerated men I'm speaking to visibly shaken. The stellar beauty of the soaring Nocturne melody is cut down by the noise of explosions. War is evil, always evil. What did the musicians do to deserve their fate? What did the residents of Warsaw do to deserve being killed by German bombs? Nothing. War is a calamity that has to be survived. Living with the stigma of incarceration requires survival skills too. It requires a lot of courage - shown by the pianist in the film and the character's real-life model. It requires a persistent clinging to life, the good life.

I pan forward to another favorite scene in the film: the famous Ballade that Szpilman played for the German officer. This has to be one of the most famous music scenes in the whole history of film-making. When the can of pickles falls down from the pale, think hands of the starving musician and rolls to the feet of the uniformed German officer... when the gaze of the emaciated, long-haired pianist dressed in rags meets the eyes of the proud soldier... Then, the pianist begins to play and the Ballade takes them both on a journey. Away from destruction, away from hunger and suffering - somewhere else.

Here, courage and humanity triumph. The officer has to break his laws and his orders if he wants to save the life of the starving pianist. He does so, moved by Chopin's music that brought him back to the time when there was no war, only life and happiness. He must have heard such beautiful music at home, before the tragedy began. The extraordinary courage of the pianist, the compassion of the "enemy" and the drama of the music speak directly to the heart. Would the lesson stick? I do not know, I can only try to share it.

Is it worth my time? I hear comments: "lock them up and throw away the key." Not everyone behind bars committed, serious violent crimes and those who did would have been sent to the prisons, not jails. Once they did something wrong, paid the price for it and returned to the society "rehabilitated" - their sentences are supposed to be over and a new life is supposed to begin. But more often than not, it does not. They cannot find jobs, cannot earn a living, cannot function. Some are willingly returning to drug dealing or stealing. Others feel cornered, feel they have no option. If they do it the second time, the sentence will be longer, the return to the "narrow path" harder. I do not write it to excuse them. But it is important for them to know that they can stay on the "narrow path" of honest life, if they make some sacrifices, just like Chopin had to make sacrifices in order to continue to compose. What other option do we have?

Looking for Chopin and the beauty of his music everywhere - in concert halls, poetry, films, and more. In 2010 we celebrated his 200th birthday with an anthology of 123 poems. Here, we'll follow the music's echoes in the hearts and minds of poets and artists, musicians and listeners... Who knows what we'll find?

Thursday, April 26, 2012

Wednesday, April 4, 2012

Chopin's Revolutionary Etude in a California Jail (Vol. 3, No. 5)

On March 26, 2012, I started a new adventure - teaching a class on art and ethics to inmates of Pitchess Detention Center in Castaic, CA. I designed my four-part class as lessons in connecting feelings to thoughts, to teach virtues by using artwork, music, and poetry - a full range of artistic experiences. I called it EVA, or Ethics and Values in Art.

On March 26, 2012, I started a new adventure - teaching a class on art and ethics to inmates of Pitchess Detention Center in Castaic, CA. I designed my four-part class as lessons in connecting feelings to thoughts, to teach virtues by using artwork, music, and poetry - a full range of artistic experiences. I called it EVA, or Ethics and Values in Art.The core framework is provided by the Four Cardinal Virtues - courage, justice, wisdom or prudence and moderation, or temperance. Known since antiquity and used to teach moral values and character through over two thousand years of Western history, the virtues have largely been forgotten. Their presence in the lives of artists and their artwork is very strong, from Rembrandt to Chopin... In planning the classes I associated each virtue with an emotion - grief, shame, joy and calm - and with a moral action - compassion, forgiveness, generosity and gratitude...

While designing the curriculum, I thought I would be teaching women, so I was quite surprised when I was assigned to a men's institution. At Pitchess, they have been given a chance to think through their decisions and change their lives. The group I'm working with has decided to do exactly that. They enrolled in and graduated from the MERIT-WISE program, a part of the Sheriff's Education-Based Incarceration project. In some ways, these men have the best chance for a successful life after completing their "time out" to rethink their life choices and orientation.

In order to get ready for the challenges ahead, they participate in various workshops and classes taught by volunteers like me. The majority have never been to an art museum or a classical music concert. My goal is to help them find their way to the Hollywood Bowl . . . That and not to return to jail. How does one do that?

The Cornerstone

Justice:

Do what's right, what's fair.

Fortitude:

Keep smiling. Grin and bear.

Temperance:

Don't take more than your share.

Prudence:

Choose wisely. Think and care.

Find yourself deep in your heart

In the circle of cardinal virtues

The points of your compass

Your cornerstone.

Once you've mastered the steps,

New ones appear:

Faith: You are not alone . . .

Hope: And all shall be well . . .

Love: The very air we breathe

Where we are.

The framework I designed and teach right now is non-religious and, therefore, I skip the three Theological Virtues mentioned at the end of my poem. There is enough material for discussion, though, in the paintings of the Prodigal Son and Tobias by Rembrandt, Guernica by Picasso, City Whispers by Susan Dobay... There is enough inspiration in the Revolutionary Etude by Chopin and the Ode to Joy by Beethoven. If I put my own poetry in this context, am I acting grandiose and, as someone once called me (to my immense delight) - a megalomaniac? The point is to find yourself in your own words. I may "know" what's out there or what I've been taught, but I truly know only what I have experienced myself. I have to go deep inside, to the truth about me, to express a vision of the world that is both deeply personal and unique in my poetry.

The framework I designed and teach right now is non-religious and, therefore, I skip the three Theological Virtues mentioned at the end of my poem. There is enough material for discussion, though, in the paintings of the Prodigal Son and Tobias by Rembrandt, Guernica by Picasso, City Whispers by Susan Dobay... There is enough inspiration in the Revolutionary Etude by Chopin and the Ode to Joy by Beethoven. If I put my own poetry in this context, am I acting grandiose and, as someone once called me (to my immense delight) - a megalomaniac? The point is to find yourself in your own words. I may "know" what's out there or what I've been taught, but I truly know only what I have experienced myself. I have to go deep inside, to the truth about me, to express a vision of the world that is both deeply personal and unique in my poetry.Non Omnis Moriar

Only the best will remain.

Startled by beauty

I fly into the eye of goodness.

Only the best . . .

Wasted hours, words, signs,

Sounds and fake symbols.

Only:

Blue torrents of feeling

Crystallized in empty space

Twisted above our heads

Where light freezes

Into sculpted infinity

Oh,

If I could be there

Once

____________________________________

If only... To open their eyes and ears to new worlds, I take my students in blue prison garb on a wild tour of the most astounding creations of the human mind. The very first piece of music they hear is the "Revolutionary Etude" - Op. 10 No. 12, a lightning strike of a piece, designed to shake up and awaken... There applause at the end is intense. The majority has never heard anything like it.

One man said, "thank you so much! This is my most favorite piece in all music, in all the world." He had asked for Chopin in the previous class and was beyond himself with delight when his unspoken wish was answered. I asked him to explain the piece to the class and put it in context. He knew enough to talk about Chopin's rage at the war, Poland being attacked by Russia, the composer's loneliness in Paris. He also thought about expressing anger and other powerful emotions in art as a positive way of responding to something that is overwhelming and destructive. From the feeling of despair at the unfairness of the world and Poland's tragic defeat to an unprecedented masterpiece.

One man said, "thank you so much! This is my most favorite piece in all music, in all the world." He had asked for Chopin in the previous class and was beyond himself with delight when his unspoken wish was answered. I asked him to explain the piece to the class and put it in context. He knew enough to talk about Chopin's rage at the war, Poland being attacked by Russia, the composer's loneliness in Paris. He also thought about expressing anger and other powerful emotions in art as a positive way of responding to something that is overwhelming and destructive. From the feeling of despair at the unfairness of the world and Poland's tragic defeat to an unprecedented masterpiece. I did not ask, why, if he was so educated and knew so much, was he there, sentenced to jail... Everyone makes mistakes. Some more serious than others. My presence among the inmates is to help them use their time as a turning point, find a new path for the future. I use classical and romantic masterpieces to show criminals that they can and should remake themselves and live a different life. How different? Are they going to learn to play the piano and become Chopin experts? Not really, but they can learn from his courage, his fortitude. He composed while spitting blood, sick with TB since the age of 16. Suffering all his mature life, he died prematurely, but left for us timeless treasures.

Etudes are, in essence, practice exercises; they are designed to learn certain skills, solve particular technical problems - arpeggios, chordal patterns, layering of melodies, the use of specific fingers. Practice makes perfect. After 10,000 hours of practicing a skill, we may become experts in it, as Malcolm Gladwell assures us. That is another lesson for offenders serving their sentences. Moral character takes time and effort to develop. Even the least educated inmates in the Los Angeles County jail may be inspired by the perfection of Chopin's art, transforming a humble exercise into a perfectly structured and intensely emotional artwork that has and will survive the ravages of time.

Versions (Pollini's is my favorite):

Svatoslav Richter: extremely fast and apparently transposed a halftone higher, the image does not go with the sound

Stanislaw Bunin: not technically perfect, but immensely popular, 2:33

Janusz Olejniczak: The phrase endings are somewhat rushed, but the drama is immense! 2:33

Maurizio Pollini: as dramatic and tender as it has to be, with great climaxes, and a score to follow, 2:49

_________________________________

Photos from Big Tujunga Wash (c) 2012 by Maja Trochimczyk

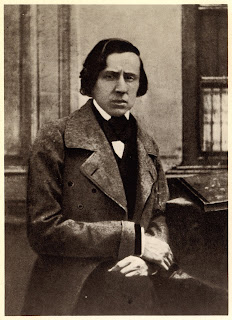

Chopin's last known photograph - daguerreotype by Louis-Auguste Bisson, 1849.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)